The Wise Wife by Megan Ann Schreibner Book Reviews

Fiction – paperback; Scribner; 191 pages; 2021.

If anything positive is to come out of the Covid-xix global pandemic it is that Australian citizens, locked out of their own country (or even their home state) cheers to edge closures, might gain a better appreciation of what it is to have freedom of movement.

Maybe they might even develop greater empathy and pity for migrants and refugees struggling to notice a new homeland in which to make a better life for themselves.

This was front and centre of my mind when reading Infinite Land, a timely novel nigh immigration, by Patricia Engel, considering so much of information technology charts the despair, frustration and feet of families separated by borders.

In this instance, the family is from Colombia. Young married couple Mauro and Elena and their infant daughter Karina flee the violence in Bogotá to make a fresh start in the United states of america.

But over the course of the side by side fifteen or so years, things don't always go according to plan, and their hopes and dreams are stifled by racism, exploitation and, when their temporary visas run out, fear of arrest and displacement. This fear later spreads to their The states-born children who are "undocumented illegals".

On the run

The story opens with a killer first line:

It was her idea to tie up the nun.

This is where we meet Talia, a 15-year-old Colombian, making her escape from a correctional facility for adolescent girls loftier upwards in the mountains. Talia has been sent to the facility for committing a horrendously violent, but spontaneous, human activity that may or may not have been warranted.

But now she's on a mission to get dorsum to her father'southward flat in Bogotá so that she can pick up the airplane ticket that is waiting for her — that ticket will get her to the U.s.a., where her mother and two older siblings live.

Talia's frantic road take a chance, hitchhiking beyond the country while avoiding the authorities, is interleaved with her parent's dearest story, including their journey to the US to begin afresh long before Talia was built-in.

These two narrative threads come together when we discover that US-born Talia was sent back to Republic of colombia as babe to be raised by her grandmother. This conclusion, based on economics, means the family at present straddles two countries — and 2 different worlds — and because of legal problems in that location is no freedom to move between them.

Exposing the myths

Space Country is excellent at exposing the myth of the United states every bit a gilt country of opportunity and as a place of rubber.

What was it nearly this country that kept everyone hostage to its fantasy? The previous month, on its own soil, an American homo went to his job at a institute and gunned down xiv coworkers, and last spring solitary there were four different school shootings. A nation at war with itself, all the same people even so spoke of it as some kind of paradise.

As the family struggles to find work and adaptation, moving from one unsecure job to another, from one lot of overcrowded adaptation to another (at ane stage they live in their automobile, in another they share a unmarried room above a pizza shop with a Pakistani couple), their situation never seems to improve.

Both Elena and Mauro are exploited as cheap labour, unable to afford a decent place to live and constantly on guard for potential deportation. Social and economical mobility is non-existent. Even educational opportunities are limited.

And the option to go dorsum is non an pick at all.

Going domicile was never an option for these women. When Elena brought upwardly the possibility of packing up, taking the children to Colombia […], Norma [a fellow immigrant] warned: 'This is a chance you won't get again. Every adult female who has e'er gone back for the sake of keeping her family together regrets it. You are already here. So are your children. It is better to invest in this new life, considering if you return to the old one, in the future your children may never forgive you.'

Despite this, Elena is torn. She would beloved to go back to see her hardworking mother, to raise her daughter, and is "never sure if she'd made the correct determination in staying". She is plagued by guilt.

Eventually, she'd understand that in matters of migration, even accidental, no option is more moral than another. There is only the path you make. Any other would exist simply every bit wrong or correct.

The price of migration

And, equally much every bit immigrating is seen every bit a chance at a improve life, it comes at a cost. This is how Mauro wants to convey it to his daughter Talia simply as she's about to board the plane to exist reunited with her female parent after xv years:

What he wanted to say was that something is e'er lost; even when we are the ones migrating, we finish up being occupied. […] What she didn't know, Mauro idea, was that afterward the enchantment of life in a new state dwindles, a detail pain awaits. Emigration was a peeling away of the peel. An undoing. You wake each morning time and forget where yous are, who you lot are, and when the world exterior shows y'all your reflection, it's ugly and distorted; you've get a scorned and unwanted animate being.

Infinite State is eloquently written and brims with humanity, compassion and cold, hard truths — information technology'south completely gratis of sentiment and withal it is powerful and moving.

I ate information technology up in a single mean solar day. And I love that it ends on a hopeful note.

If you liked this, you might besides similar:

'The Book of Unknown Americans' by Cristina Henriquez: A story about two immigrant families from Latin America facing racism, victimisation and poverty as they endeavour to forge new lives in the Us.

'Signs Preceding the End of the World' past Yuri Herrera: This occasionally violent novella focuses on a young Mexican woman who illegally enters the The states to search for the brother who had gone there to "settle some business concern" for an underworld effigy.

'The Tortilla Mantle' by T.C. Boyle: A compelling story that showcases the stark departure between the haves, in this example a rich American family living on a gated estate in California, and the take nots, a young Mexican couple hiding out in a nearby canyon having crossed the border illegally.

Fiction – paperback; Picador; 342 pages; 2010.

Last year I read John Banville'due south latest novel, Apr in Espana, a marvellous law-breaking-inspired romp set in San Sebastian in the 1950s.

But while I recognised the connections with his Quirke Dublin serial penned nether his law-breaking-writing pseudonym, Benjamin Blackness, and his magnificent locked room mystery Snow, I failed to see that it was basically a follow-up to his novel Elegy for April, published more than a decade agone.

I simply discovered this fact when browsing in my local second-mitt book warehouse and Elegy for April was staring at me on the shelves! So information technology came home with me (in substitution for $nine.90) and I've spent the best office of the last week reading it and eking out the story for as long as possible because I was enjoying it so much.

A adult female vanishes

Set in Dublin in the 1950s, this richly atmospheric tale focuses on the mysterious disappearance of a junior doctor, April Latimer, and explores what might have happened to her.

Was she murdered, or did she stage her ain disappearance? And regardless of the scenario, what caused her to vanish? There's no torso to be found, no sign of struggle or foul play.

Her family unit — a stuck-up female parent, a pretentious brother and an uncle who is a government minister — don't seem to care, arguing that April had long chosen to disassociate herself from her family unit for personal reasons and she's probably only gone off with a man or escaped for a holiday in the sunday.

Only her circle of friends are concerned because it is unlike April to not attend their drinking sessions and become-togethers without telling them first. Her friend Phoebe Griffin is and then worried she asks her begetter, the pathologist Quirke, to help determine what might have happened.

Genre busting novel

This novel isn't a police procedural, nor is it a traditional detective story. It's Banville'south own accept on crime but information technology's by no means a conventional criminal offense novel per se. The reader tin't fifty-fifty be sure that a crime has taken place. At that place's certainly no neat resolution, with all the loose stories lines tied up at the finish.

But Elegy for April is a wonderfully evocative read and what it lacks in plot information technology makes up for in characterisation. It is peopled with a cast of distinctly colourful characters, including the star of the testify, Quirke, whose orphaned childhood and complex, and oftentimes strained, family relationships have shaped his outlook on life and which provide a rich back story for Banville to explore.

When the book opens, for instance, nosotros discover that Quirke is just finishing a stint at St John of the Cross, a "refuge for addicts of all kinds", because of his penchant for booze. Throughout the novel, he wrestles with his newfound sobriety, convincing himself that one or two drinks won't hurt — ofttimes with disastrous, and occasionally, hilarious results.

And while he's adjusting to life as a teetotaler, he'south also adjusting to life every bit a father, for when Quirke's wife died in childbirth, he gave away his infant girl to his sister-in-constabulary and kept it hugger-mugger from the kid, Phoebe, who has only recently learned of the truth. The pair are trying out their newfound father-girl relationship with tender but laboured efforts.

Portrait of 1950s Dublin

The story paints a vivid portrait of 1950s Dublin — the streets, the pubs, the landmarks — and gild's moral stance on such things as inter-racial relationships (was Apr Latimer, for instance, having relations with a black Nigerian human?), abortion and single women.

And while it's a serious story nigh a potential murder, it'due south besides incredibly funny in places. Quirke, for instance, buys a car — a very expensive and rare Alvis TC108 Super Graber Coupe, "one of merely iii manufactured so far" (Wikipedia picture) — even though he does non know how to drive and doesn't have a licence. His scenes behind the wheel are hilarious.

At the corner of Clare Street, a boy with a schoolbag on his back stepped off the pavement into the street. When he heard the blare of the horn he stopped in surprise and turned and watched with what seemed mild curiosity as the sleek black auto bore downward on him with its nose low to the ground and its tyres smoking and the 2 men gaping at him from behind the windscreen, one of them grimacing with the attempt of braking and the other with a paw to his head. 'God almighty, Quirke!' Malachy cried, as Quirke wrenched the steering wheel violently to the right and back again.

Quirke looked in the mirror. The boy was still standing in the middle of the road, shouting something after them. 'Yes,' he said thoughtfully, 'information technology wouldn't do to run ane of them down. They're probably all counted in these parts.'

And as ever with a Banville novel, the prose is beautiful and dotted with highly original similies throughout.

Quirke, for case, standing in his long black coat and black hat resembles a "blackened stump of a tree that had been blasted by lightning"; a phase actress with whom Quirke has a fling has brilliant red lips "sharply curved and glistening, that looked as if a rare and exotic butterfly had settled on her rima oris and clung there, twitching and throbbing"; while a underground between lovers that is never discussed but always remains between them is described equally "like a light shining uncertainly distant in a dark forest".

I thoroughly enjoyed Elegy for April and look frontwards to reading more than in this Quirke serial as soon every bit I can lay my hands on them.

I read this volume as part of Cathy's #ReadingIrelandMonth2022. You tin find out more about this almanac blog upshot at Cathy's weblog 746 Books.

I read this volume as part of Cathy's #ReadingIrelandMonth2022. You tin find out more about this almanac blog upshot at Cathy's weblog 746 Books.

DRUM Curlicue, Delight.

Reading Matters is at present 18.

Yea, I can't believe it either. If this weblog was a person, she'd be onetime plenty to vote, drive a car, buy alcohol and become into nightclubs. Where did the fourth dimension get?

I've been doing this malarkey for so long, usually on peak of a busy solar day job (of which I take had many over the years), that I can't really remember what I used to do in my spare fourth dimension earlier it.

Blogging about books has been a much-cherished creative outlet. It'southward taught me discipline, helped hone my online skills, improved my writing and editing, and made me a more critical reader. And it's as well introduced me to a supportive community of fellow bloggers, readers, writers and publishers I might non otherwise have met.

Blogging about books has been a much-cherished creative outlet. It'southward taught me discipline, helped hone my online skills, improved my writing and editing, and made me a more critical reader. And it's as well introduced me to a supportive community of fellow bloggers, readers, writers and publishers I might non otherwise have met.

I recently had to explicate a signal of difference near my blog from the millions that at present exist, and I summed information technology up equally being "one of the world'south commencement blogs about books".

When I started Reading Matters back in early 2004, blogging was a new form of media, the first step in the democratisation of publishing.

Everything almost it was apprentice. There was no such thing every bit an "influencer". Social media didn't be. The release of the first iPhone was still three years away. The volume industry didn't know virtually blogging or hadn't yet cottoned on to how they could use bloggers to assist them spread the word about their wares.

It was a brilliant time of discovery and fun and it was relatively gratis from commercial agendas, external forces and self-promotion. We were all just figuring it out as we went forth.

As a print announcer, I institute information technology a applied manner to teach myself new skills that might aid me suspension into the digital world. But back then the print media hated new media, which information technology viewed as a threat — rightly every bit it turns out — but I was excited to have a foot in both camps.

Over the years people accept occasionally asked me to share tips or expertise on book blogging and I've ever shied away from it. I don't see myself equally an expert. I'thou simply a passionate reader who found an outlet for sharing that passion online. I don't, for case, have an Arts caste, have never studied English literature and am not well-read in the Classics. And everything I know about blogging (and reviewing books), I but learned along the way, mainly through trial and error.

Just the beauty of blogging is that there are no "rules" — except the ones y'all set yourself.

I've always tried to espouse the same kinds of values here in the online world that I do in my real offline life: I exercise my ain affair; I don't follow fashions or fads; I try to be respectful of other people's points of view fifty-fifty if I don't hold with them; I am always aware that any work I review here has taken hours of difficult graft by a real person and so any criticism should be constructive and not-personal; I am transparent and don't push agendas considering integrity is important; I try to be kind and courteous but I call out bullshit when I see information technology; I like to encourage and help others and spread the love wherever possible; and I ever aim to exist fair and balanced.

A few key things I have learned, merely which are probably obvious to others, include:

- it's not quantity (of content) but the quality that counts;

- stats don't make the world go round;

- having a set up schedule isn't important — you tin take a twelvemonth off if you similar, in the grand scheme of things it's non going to matter — and there's no need to apologise for an online absence, you don't owe anyone anything;

- there's no need to post every day because some "adept" claims y'all will lose "traffic" if you don't, just do it when you feel like information technology, information technology'due south a hobby NOT a job;

- if you're struggling to write a review take a rest, come up back subsequently or just quit, yous don't get points for being a masochist;

- you don't demand to review everything that is sent to you (provided y'all haven't fabricated any promises) — feeling guilty about this just eats up energy better devoted elsewhere and 18-carat publishers understand that real life gets in the style and they'll only be happy if a sure pct of books that they ship out get reviewed, they're not expecting a 100 per cent strike-rate;

and *finally*

- don't get hung upwardly about how many books are in the TBR or how much money you have spent on books — you could accept a far worse addiction, similar scoring crack cocaine!

I'm sure there are loads more "lessons", but this post has gone on way too long already. And if you are even so reading, thanks for hanging in there.

Thanks, besides, to everyone who has followed this web log (and the associated Facebook page), left a comment, sent me an e-mail or a volume, invited me to bookish things on the basis of what I exercise hither, or told others about my reviews. It'southward all appreciated — and makes the solitary process of tapping out words on a laptop, on the evening or weekend, that little bit more communal.

Finally, I love this quote by American academic

Books are the quietest and most constant of friends; they are the most attainable and wisest of counselors, and the near patient of teachers.

Yous could say the aforementioned about book blogging, right?

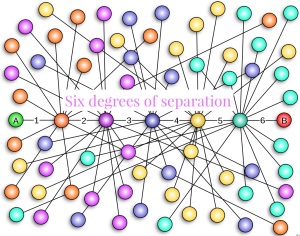

It's been a couple of months since I participated in Vi Degrees of Separation^. Information technology e'er seems to sneak up on me so I lose the energy or inclination to take part. I've been feeling decidedly lacklustre of late and this calendar week I discovered why: I am anemic and my Vitamin D levels are low. Then on to the loftier-dose supplements, nether my GP's supervision, we get — and after a few days' dosage, I'g already feeling better (although I know it'south going to take months to go my iron levels upward).

It's been a couple of months since I participated in Vi Degrees of Separation^. Information technology e'er seems to sneak up on me so I lose the energy or inclination to take part. I've been feeling decidedly lacklustre of late and this calendar week I discovered why: I am anemic and my Vitamin D levels are low. Then on to the loftier-dose supplements, nether my GP's supervision, we get — and after a few days' dosage, I'g already feeling better (although I know it'south going to take months to go my iron levels upward).

Only anyway, on with the evidence! As always, click the title to read my full review of each book.

This month the starting volume is…

'The End of the Affair' by Graham Greene (1951)

This nighttime simply compelling tale is near a doomed dearest affair that takes identify in 1940s war-torn London. Maurice Bendrix, a successful author, falls for Sarah Miles, the wife of a dreary ceremonious servant with whom he has struck up a business relationship. For five years Maurice and Sarah behave an illicit, passionate affair until Sarah calls it off without warning or explanation.

Some other book about a love affair during the 2d World War is…

'Off-white Stood the Air current for French republic' by H.East. Bates (1944)

I ever describe this novel equally the loveliest volume about state of war you will ever read. It tells the story of a Royal Airforce airplane pilot who crash lands in Occupied France, together with his coiffure of four, and is nursed back to health by a immature woman with whom he falls in honey. It'southward not a sappy romance, though, for in that location are dangers lurking everywhere — can the woman and her family unit be trusted not to beguile them to the Germans, for instance — and the pilot is caught in a heart-breaking dliemma: should he stay or should he become?

Another book nearly forbidden love in French republic is…

'Prevarication With Me' by Philippe Besson (2019)

This modern romance is virtually get-go beloved between 2 teenage boys in rural French republic in the 1980s. Their thing, kept hidden considering of the shame surrounding homosexuality at the fourth dimension, begins in winter simply is over past the summertime. During those few intense months, their love is passionate merely furtive. For both boys, it is a sexual enkindling that has long-lasting repercussions on how they live the balance of their lives.

Another book almost gay love in prejudiced times is…

'Fairyland' by Sumner Locke Elliott (1990)

Published subsequently the writer's death, this novel is supposedly a thinly veiled memoir based on his first-hand experience keeping his homosexuality cloak-and-dagger. Set largely in Sydney, the book explores what it is like to grow up in the 1930s and 40s hiding your real cocky from the world. Information technology is a heart-rending, intimate and harrowing portrayal of ane man'southward search for love in an atmosphere plagued by the fear of condemnation, violence, prosecution and imprisonment.

Another novel with similar themes is…

'The Waking of Willie Ryan' by John Broderick (1963)

This story — of a human being who escapes an asylum in rural Ireland to confront the people who put him there — is a damning indictment of how easy it in one case was to remove troublesome people from gild by only labelling them "insane". Willie is non insane and probably never has been. But he has dark secrets, well-nigh his babyhood, about his love for some other homo, about the existent reason he was incarcerated in a mental institution all those years ago.

Another book about escaping from a psychiatric unit is…

'My Friend Fox' by Heidi Everett (2021)

In this evocative memoir, we learn what it is like to be a resident on a psych ward, where every facet of your life is controlled by rigid medical protocols and unwritten rules. Everett has spent much of her developed life in and out of psychiatric institutions. Her story shows the devastating impact of mental illness on one person's life, but despite the trauma at its heart, this survivor'southward tale brims with hope and optimism.

Another memoir about a adult female struggling with mental illness is…

'Your Voice in my Caput' by Emma Forrest (2012)

Emma Forrest was a successful young music journalist when she tried to have her own life. She developed a close relationship with her therapist, only when he died unexpectedly (of lung cancer) she was left distraught. This memoir is not only an unflinchingly honest account of her psychiatric bug, it's an insightful look at grief and what it is like when a patient loses someone they trust and rely upon. Oh, and it's besides almost a doomed dearest thing — with the Irish gaelic actor Colin Farrell who is referred to as GH (which stands for Gypsy Husband) throughout.

So that'south this month's #6Degrees: from a novel about a doomed dearest affair to a memoir well-nigh a doomed love thing, via tales of forbidden honey and a memoir about life on a psychiatric unit.

Have you read any of these books?

Please note, y'all tin meet all my other Six Degrees of Separation contributions hither.

^ Bank check out Kate'south web log to find out the "rules" and how to participate.

Fiction – hardcover; Weidenfeld & Nicholson; 148 pages; 2020.

This is why I love browsing in the library and then much; I would not have discovered Cathy Sweeney's Modern Times otherwise.

First published in the Commonwealth of Republic of ireland by Stinging Wing Press and now reissued past W&Northward, information technology is a drove of brusque stories with an absurdist and often risqué slant.

The suggestive encompass art — designed by Steve Marking / Orion — is perfectly appropriate, for the very first story, "Love Story", opens similar this:

There was in one case a woman who loved her husband's cøck^ so much that she began taking it to work in her lunchbox.

How's that for an opening line?

Tales about taboo subjects

In that location are other stories that revolve effectually sex and love affairs and animalism. Well-nigh are only a few pages long, simply they are shocking, against and wickedly funny past turn.

In "The Birthday Present", for example, a adult female buys her husband a sex doll chosen Tina for his 57th birthday and keeps it locked in the guest room for his personal amusement. Only when he dies unexpectedly, she has to proceed "Tina" subconscious from her developed children.

In "The Handyman" a divorcee wonders what information technology would be similar to have sex with the handyman she invites into her semi-detached house to prepare upwards a few things before putting it on the market place, while in "A Theory of Forms" a teacher reminisces about the illicit sex she used to have with a teenage boy who had learning difficulties.

In "The Woman with too Many Mouths", a man plans to end his affair with a adult female who has two mouths — "She was, as I said, not my blazon" — while in "The Chair", a married couple accept it in turns to administer electric shocks as a substitute for sex:

When it is my plough to sit down in the chair, I am virtually relieved. In the days leading upwards to it I become irritable, angry, even on occasion experiencing vehement ideations. Often, during this menses, I recollect of leaving my husband, of breaking everything. But when the fourth dimension comes to sit in the chair I do and so without protestation. A sensation of release and expanse overtakes me, as though I am swimming effortlessly in a vast blue ocean, obeying laws of nature that are larger than me, larger than the universe.

A little scrap bonkers

Non all the stories are framed around these taboo subjects. Some are truly bizarre and best described as OFF THE WALL, bonkers or just plain WIERD.

There'southward a story about a palace that becomes sick evident by a "dark discolouration" spreading through the bricks at the summit of its tower. Another story revolves around a manuscript that is plant wrapped in newspaper and hidden behind a banality in a house recently "vacated" by an old man. In some other, a son returns from boarding schoolhouse and is instructed to supervise his mother at a family commemoration for fear she will get up to "her old antics, letting the whole family down".

Out of the 21 stories in the collection, my favourite is "The Woman Whose Kid Was A Very Sometime Man" in which an unmarried mother escaping a "dull provincial backwater" moves to a urban center bedsit and takes a job at a local shop. She can't afford childcare, so while she is at piece of work she puts her baby in the freezer and every bit soon equally she gets domicile she thaws him out.

Well, human being nature is human nature, and annihilation can go normal. Soon putting the babe in the freezer was part of the rhythm of life. There were no various side effects. The baby went into arrested development while frozen, but then caught up easily when thawed out. When the woman had a day off the babe sometimes outgrew a romper suit in an afternoon or learned to crawl in an hour.

Eventually, this pattern of freezing and growing gets out of whack, and the child grows — and ages — too quickly. And then the woman gets distracted by her new career as a writer and forgets her child in the freezer, just to return years later to discover he's become a very sometime man. Yeah, I told you the stories were bonkers.

Wholly original

The blurb on my edition suggests that Sweeney'due south stories are reminiscent of Lydia Davis, Daisy Johnson and Angela Carter, just having but read Carter's The Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault I don't know how accurate that comparison is. They do bring to mind the genius that is Magnus Mills, perhaps considering of the simple, fable-like prose in which they are written. Regardless, they are wholly original — and totally memorable.

Modernistic Times is a refreshing palate cleanser offering a quirky, inventive have on the short story. It is not bad fun to read! I promise Sweeney writes a novel next so she can give extended reign to that vivid imagination!

^ I've inserted a special character so my content isn't deemed "unsafe" by search engines.

I read this book every bit office of Cathy's #ReadingIrelandMonth2022. You can find out more nigh this annual blog event at Cathy'due south blog 746 Books.

I read this book every bit office of Cathy's #ReadingIrelandMonth2022. You can find out more nigh this annual blog event at Cathy'due south blog 746 Books.

The Stella Prize longlist for 2022 has just been announced.

The Stella Prize longlist for 2022 has just been announced.

This is the 10th year of the prize, which is open to Australian women and non-binary writers. All genres, including fiction and non-fiction, are eligible, but this is the starting time twelvemonth that verse has been included.

There are four poetry collections on the longlist, as well equally two brusk-story collections, two non-fiction books, an essay, a graphic novel and two novels.

Interestingly, out of the 12 books longlisted, vii are debuts and five are by First Nation writers.

This is what is on the list:

- Coming of Historic period in the War on Terrorby Randa Abdel-Fattah (non-fiction, NewSouth Books)

- Take Intendance by Eunice Andrada (verse, Giramondo Publishing)

- Dropbearby Evelyn Araluen (poetry, University of Queensland Press)

- She Is Hauntedby Paige Clark (brusk stories, Allen & Unwin)

- No Documentby Anwen Crawford (essay, Giramondo Publishing)

- Bodies of Lightby Jennifer Downwards (novel. Text Publishing)

- Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhurayby Anita Heiss (novel, Simon & Schuster)

- Stone Fruitby Lee Lai (graphic novel, Fantagraphics)

- Permafrostby SJ Norman (short stories, Academy of Queensland Press)

- Homecomingby Elfie Shiosaki (poetry, Magabala Books)

- The Openby Lucy Van (poetry, Cordite Books)

- Some other Twenty-four hours in the Colonyby Chelsea Watego (non-fiction, University of Queensland Press)

I haven't read anything on the listing, which isn't surprising seeing as my focus is more often than not on literary fiction and in that location's only two novels on this listing. I will wait until the shortlist is announced on 31 March earlier deciding whether to read the entire shortlist as I have occasionally washed in other years.

The $l,000 prize will be appear on Thursday 28 Apr.

In the meantime, you tin can find out more than about the longlist announcement here and read the judge's report hither.

Fiction – paperback; Penguin; 176 pages; 2009.

Robert Drewe was born in Melbourne in 1943, grew up in Western Australia and became an award-winning journalist on the e coast before he turned his mitt to fiction. The Bodysurfers, beginning published in 1983, is a collection of loosely connected short stories and I loved information technology.

There are 12 in total, each around 10 pages long, and they are mainly fix in the coastal suburbs of Perth and Sydney, though there's besides a story set on the Californian coast. The beach is a central theme (surprise, surprise) and there are lush, vivid descriptions of the sandhills, the surf and the dangers that lurk within.

Intrigued as I am past the ocean, I am not an enthusiastic surf swimmer. […] Surf and tides turn malign as well suddenly, waves dump yous, sandbanks crumble in the current, undertows can take hold of you unawares. […] Information technology isn't the waves or the undertow that worry me when I do, still — it'south sharks. I imagine they're everywhere. In every kelp patch, in the lip of every billow, I sense a shark. Every shadow and submerged stone becomes ane; the sparse feather of spay on the edge of my vision is scant alarm of its final lunge.

And while the stories are varied in style and point-of-view (some are third-person, others are get-go-person, and one — Sweetlip — is written in the mode of a confidential report), the ways in which men navigate inverse circumstances is a primal focus. In these tales, men lose jobs, lose wives, lose their sense of purpose or pride.

In one story a prisoner adjusts to life outside by ogling bare-breasted women at the beach, in another a man has an affair with a woman whom he suspects is cheating on him.

In Shark Logic a human being stages his ain disappearance following financial irregularities at the school at which he was the headmaster and begins living a low-cardinal invisible life by the ocean; in The Last Explorer an elderly human being lying in his hospital bed recalls his past achievements — specifically crossing the continent from eastward to west in a 10-year-one-time Model T-Ford in the 1920s — and cringes when the nursing staff ask if he's "done a wee this morning".

The Lang family unit chronicles

And threaded throughout these diverse tales are recurring characters from three generations of the same family. We meet the Langs in the opening story, The Manageress and the Delusion, when three children — Annie, David and Max — are taken to a beachside hotel for their first Christmas dinner subsequently their female parent'due south expiry. Their father, Rex, is keen to maintain sure festive traditions, merely what he doesn't tell them is that he is having an thing with the hotel manageress, a nighttime-haired woman in her 30s, who pays them too much attention and actually joins them for dinner.

And threaded throughout these diverse tales are recurring characters from three generations of the same family. We meet the Langs in the opening story, The Manageress and the Delusion, when three children — Annie, David and Max — are taken to a beachside hotel for their first Christmas dinner subsequently their female parent'due south expiry. Their father, Rex, is keen to maintain sure festive traditions, merely what he doesn't tell them is that he is having an thing with the hotel manageress, a nighttime-haired woman in her 30s, who pays them too much attention and actually joins them for dinner.

She announced to me, 'You do expect similar your father, Max'. She remarked on Annie'south pretty hair and on the importance of David looking after his new watch. Sportively, she donned a blue paper crown and looked at us over the rim of her champagne glass. As the plum pudding was being served she left the table and returned with gifts for us wrapped in aureate paper — fountain pens for David and me, a doll for Annie. Surprised, nosotros looked at Dad for confirmation. He showed little surprise at the gifts, however, only polite gratitude, entoning several times, 'Very, very kind of you'.

In later stories, we meet Max and David as adults, navigating their own marital issues and affairs, and in some other — named Lxxx Per Cent Humidity — information technology's David's son Paul who plays a starring role:

On Paul Lang's worst day since existence extruded from the employment market he makes several bad discoveries. In ascending order of disruption and confusion rather than chronologically they are flat battery in his onetime Toyota, the lump on his penis and the lesbian love poem in his girlfriend's handbag.

This loose drove of stories offers an insightful glimpse into the lives, attitudes and obsessions of white middle-form heterosexual Australian men from the mid-20th century to the early 1980s. They're occasionally witty, sometimes terrifying and oft focused on jealousy, love, lust or death.

The Bodysurfers has been adjusted for moving picture, television, radio and the theatre. I take seen none of them.

I read this volume as part of my #FocusOnWesternAustralianWriters. Yous can find out more than about my ongoing reading project hereand see what books I've reviewed from this part of the world on my Focus on Western Australian folio.

I read this volume as part of my #FocusOnWesternAustralianWriters. Yous can find out more than about my ongoing reading project hereand see what books I've reviewed from this part of the world on my Focus on Western Australian folio.

Fiction – paperback; Allen & Unwin; 320 pages; 2021.

Australian writer Michelle de Kretser's latest title, Scary Monsters, is an intriguing object. It is a book of two halves and boasts two forepart covers — a luscious-looking carmine on i side and a pretty cherry tree in bloom on the other — and the reader gets to choose which story to start with showtime.

One story is ready in the past — France in 1981 — and the other is set in the near time to come in an alternative Australian reality.

It's non obvious how the stories are linked other than both riff on the idea of immigration and what it is to exist a South Asian immigrant in Australian club.

I opted to get-go with the Australian section (with the cherry tree on the cover), rather than reading the book in chronological order.

Lyle'south story

Lyle is an Asian migrant desperate to fit into Australian social club and to espouse "Australian values" wherever he tin can.

People like us volition never be invisible, so we have to make a stupendous effort to fit in.

He works for a sinister Government section, is married to an ambitious woman called Chanel, and has ii children, Sydney and Mel. His outspoken elderly female parent, Ivy, also lives with them.

In this most-future, the country is ruled past an extreme right-fly government, Islam is banned and if migrants, or their Australian-born children, step out of line they can be sent dorsum to where they came from.

Australian values are all nearly rampant consumerism, being obsessive near real estate and pursuing individualism at any toll. It is late capitalism at its very worst, only at that place are strong echoes of contemporary Australian life to make the reader sit upwardly and have find.

There is nothing subtle about this story. It'south a black one-act about ethics, morality, racism and ageism, and I may possibly accept underlined at to the lowest degree ane paragraph that resonated on every page.

"Australians are never satisfied with what they've got. They — we — ever want more. Nosotros aim for the highest, we strive. It's called aspiration."

"Information technology used to be called greed."

Lili'southward story

Lili is a young bookish who migrated to Commonwealth of australia from south-east Asia with her family as a teenager. At present she's moved to the south of France to take up a pedagogy position.

She rents a top floor apartment and is creeped out by the tenant who lives below her because he wants an intimate relationship with her, but she'southward not interested.

In the local town foursquare, she watches North African immigrants being rounded up by the gendarmes. On one occasion she is also asked to prove her identity because as a person of color in a predominately white society she's likewise singled out as foreign.

This story is more subtle and nuanced than Lyle's and examines the idea of what it is to be a "new Australian" living in Europe when your face does not lucifer the idea of what an Australian should expect like.

All his life, Derek had believed i affair about Australians, and now people like me were showing up and taking that conventionalities autonomously.

Also every bit racism, it also explores misogyny and the difficulties young women can face when living lone.

Only it ends on a hopeful note, with the election of François Mitterand on x May 1981, a left-wing politician at a time when the world was dominated by right-wing conservative governments.

Uneven novel

As a whole, I found Scary Monsters uneven because the ii different sections are just and then different in tone and manner. Perhaps the but thing they have in common is that they are both written in the first person in warm, intimate voices.

And while they explore like themes, they do it in radically unlike ways: Lyle's story is substantially speculative fiction told with biting wit, while Lili's is more akin to literary fiction and hugely reminiscent of de Kretser'southward Questions of Travel, which won the Miles Franklin Literary Award in 2013.

Which story you start with may sway your overall feeling toward the novel.

Opinions online have been polarised, every bit reviews by Lisa of ANZLitLovers and Brona of Brona's Books demonstrate.

The novel has been published in the Uk and US but with a radically different cover design.

Session at the Perth Festival "Writers Weekend", 26-27 February 2022

I bought my ticket to run into Michelle de Kretser at the Perth Festival when nosotros all idea the Western Australian border was going to come down on February 5, allowing writers from the rest of Australia to attend. A few days later Premier Mark McGowan announced the re-opening would be delayed and of a sudden the festival's lineup of writers from the eastern states was in jeopardy.

But organisers did an amazing job to ensure those writers could still appear, albeit via livestream. Ticketholders were offered refunds on this ground, but I figured information technology was still worth attending, and then this forenoon I rocked upwards to the beautiful setting of Fremantle Arts Middle, a mere two-minute stroll from my apartment, to attend Michelle de Kretser's event.

The 11.30am session undercover on the S Backyard was hosted by ABC Radio National broadcaster Kirsti Melville, who sabbatum solitary on stage while de Kretser appeared on a giant cinema screen behind her.

I'1000 not going to report on everything that de Kretser said, simply here are some of the more interesting points she mentioned:

- She wanted to set Lyle's story in the very near future rather than the distant time to come to go far more recognisable for readers.

- She described information technology as a "black one-act verging on the grotesque" and that Lyle was "the perfect mediocre Australian man", which elicited many laughs.

- Asked whether it was fun to write, she responded: "Information technology was fun." A beat later, she added: "And it was dreadful."

- She ready Lili's story in 1981 and in France because she, herself, had lived there at that fourth dimension and and then was familiar with the region and its politics. She liked the idea of ending the story with Mitterand's election win considering it felt like a "resurgence of promise".

- That era was also plagued by violence against women, specifically, the Yorkshire Ripper, which is why she explored Lili'due south safety fears and the ways in which misogyny impacts women's everyday lives.

- She wanted to write about the migrant experience, but non in a standard way considering she felt she had done that before. And she wanted to alter the representation of Australians in Europe, which are unremarkably white.

- The volume'south upside downwardly, flip-information technology-over style format is deliberate. It's supposed to be a metaphor for what happens when people drift: their lives are thrown upside downwardly and information technology can take a long fourth dimension to feel settled. She wanted the reader to experience that feeling.

- She highlighted the definition of the discussion "monster" equally something that "deviates from the norm", which is what happens to your life when y'all migrate.

- Writing the stories in the start person was something new for her every bit a writer — usually she simply uses the third person. She has been slightly wary of it because "if your character is female person, it's immediately assumed it'due south autobiographical". She started writing the volume in the third person only it wasn't working for her.

- Another challenge was ensuring that Lyle's voice was interesting because he was a deliberately bland character trying to become invisible and this is partly why she uses satire to enliven his vocalisation. She used "the language of advertising", such as brand names for people's names, to add sense of humour and colour.

- Ageism is an result that troubles her, which is why she explored this topic through the graphic symbol of Ivy. "Erstwhile women are the least valued members of guild," she said.

- She believes the aged care sector in Commonwealth of australia has been dire throughout this unabridged century, not just during the pandemic, and she was angry that the Federal Government minister for Senior Australians and Aged Care Services Richard Colbeck was withal in a job after everything that has happened in this sector during the pandemic, calling it disgraceful and shameful. She said this regime'due south contempt for the sometime was shocking.

- She is not currently working on a new novel, describing this equally her precious "fallow fourth dimension".

About PERTH FESTIVAL

Founded in 1953 by The University of Western Australia, Perth Festival is the longest-running international arts festival in Australia and Western Australia's premier cultural event. The Festival has developed a worldwide reputation for excellence in its international plan, the presentation of new works and the highest quality artistic experiences for its audience. For almost seventy years, the Festival has welcomed to Perth some of the world's greatest living artists and at present connects with hundreds of thousands of people each year.

Non-fiction; paperback; New South Publishing; 352 pages; 2020.

Perth is part of a series of books about Commonwealth of australia's majuscule cities, each one written by a local writer who can give us an intimate account of the urban center's history and character.

This volume, past Fremantle-based writer David Whish-Wilson, is an insider'south await at what information technology is like to grow up and reside in Perth, the virtually isolated city in Australia (if non the world), sandwiched as information technology is between the Indian Sea and the outback.

As about of you will know, I moved here in mid-2019. I am not from Perth (I grew up on the other side of the country, in Victoria) and had but ever been here on holiday (when I was living in the UK — Perth is a convenient city to pause up the journey from Heathrow to Melbourne). But I knew from my handful of visits to Fremantle, a port city at the oral cavity of the Swan River, about xx minutes drive from the CBD, that I would love to live here. It was something nearly the heritage buildings, the coastline, the vibrant arts culture, the pubs (and breweries) and the bright clear light that attracted me.

But more than two years after repatriation, admittedly 80% of that time during a global pandemic, I have come to know the urban center reasonably well and noticed, but not ever understood, its distinctive quirks — the fact, for instance, that most residents are early on birds, up and about at 5am, but drive through the suburbs afterwards 7pm and it feels similar the whole world has gone to bed (or died), it'south so dark and quiet, with nary a vehicle on the road.

And anybody is obsessed with the water, whether embankment or river, and virtually own a gunkhole (and are snobby about the model, the size and how much it price) or is into fishing or surfing or kayaking or stand-upwards paddleboarding (y'all get the thought).

And well-nigh people alive in the suburbs — indeed, the suburbs stretch along the coastline for more than 100km so that when you bulldoze anywhere it sometimes feels like you're out in the countryside when, in actual fact, you are however in metropolitan Perth.

And perhaps considering of this quiet, suburban life, people seem to besiege in big packs every weekend to have picnics (by the river or in local parks). I've seen people bring their ain marquees, fold-upward furniture and deport all their food and drink in wheel-a-long carts. It's fascinating. (I've long joked that I'll know I've become fully alloyed when I buy a fold-up picnic chair or one of these.)

The inside rails

The book itself isn't so much a travel guide — it won't reveal the best places to swallow or stay or visit — but is more a journey into the heart and spirit of the metropolis, highlighting its history (adept and bad), its politics, it's natural wonders and its achievements.

It's divided into four main chapters — The River, The Limestone Declension, The Plain, and The Urban center of Light — between a relatively lengthy Introduction and Postscript. Sadly, at that place'south no index, which makes information technology hard to pinpoint facts yous might want to reread (for the purposes of writing this review, for instance) and even though it has been updated since the original 2013 edition was published, it withal feels slightly dated.

Merely thanks to the good for you dollop of memoir that Whish-Wilson adds, you get a real feel for what it is like to grow upwardly hither under blue skies and abiding sunshine, and with little intrusion from the exterior world, a sense of perfect isolation.

I love all the literary references he dots throughout — there's a helpful bibliography at the back of the book — to prove how the city has been depicted in both fiction and non-fiction over time.

Unsurprisingly, given his background equally a crime writer, the author balances the happy optimism of Perth life with darker elements, including the offense and abuse that has left its marker.

He highlights the eerie Ying and Yang feeling that I had instinctively felt when I showtime arrived but had non been able to articulate because I didn't know what information technology was. Whish-Wilson frames it as people becoming untethered by the "silence and space of the suburbs" and so that while all looks quiet and peaceful during the day, it is chock with menace at night. He describes this as "Perth Gothic". (It's true there have been some hideous murders in Perth, not least the Claremont serial killings in 1996-97, the Moorhouse murders in 1986 and the Nedlands monster, who was active betwixt 1958 and 1963, and became the last man hanged in Fremantle Prison.)

All that aside, this is a brilliant lilliputian gem of a volume. Information technology's jam-packed full of insights, intriguing facts and personal observation and delivered in an intimate but authoritative voice. It's like getting the within track on what this city is similar behind the shiny glass skyscrapers and quiet, tree-lined suburban streets, and Whish-Wilson is the perfect guide.

I read this book as part of my #FocusOnWesternAustralianWriters.Y'all can find out more about my ongoing reading project hereand run into what books I've reviewed from this part of the earth on my Focus on Western Australian page.

I read this book as part of my #FocusOnWesternAustralianWriters.Y'all can find out more about my ongoing reading project hereand run into what books I've reviewed from this part of the earth on my Focus on Western Australian page.

Non-fiction – hardcover; Sandycove; 304 pages; 2021.

Like many outspoken people condemned for speaking the truth, Irish singer-songwriter Sineád O'Connor was a woman earlier her time.

When she ripped up a photo of the Pope live on American Telly in 1992 to protest sexual corruption of children past the Cosmic Church building, she was roundly castigated, her records burned and her public appearances cancelled. She became persona non grata virtually overnight. Fifty-fifty Madonna, that bastion of virtue (I jest), attacked her.

At the fourth dimension, she was a global star thanks to her cover of the Prince song Nothing Compares to U — released in 1990 (YouTube clip here) — but this single act, prescient as information technology we now know it to be (it was ix years earlier Pope John 2 acknowledged the issue), killed her international career. (Interestingly, her story about meeting Prince does not paint him in a good light.)

And yet, in the decades that take followed, she has continued to slog away, creating corking music in various different genres including pop, rock, folk, reggae and religious. And she has continued to stand upwards for what she believes in, frequently playing out her struggles — mental health issues and relationship breakdowns, for case — in total glare of the public heart.

Long fourth dimension fan

I'grand a long fourth dimension Sineád O'Connor fan. It began when I bought her debut album The Lion and The Cobra in my late teens, two years after it had been released. At the time, I was just showtime to explore Irish music, both traditional and popular, and this sounded like an intriguing blend of the two.

I wasn't wrong. This album was powerful. It was melancholy. It was cute. Information technology was aroused. And her ethereal voice, quite unlike anything I'd ever heard before, was mesmerising equally she shifted between singing like a banshee and singing like an angel, sometimes within the space of a line or a verse.

What was amazing was that she was only 20 years old when she made it. She not only wrote many of the songs herself, but she besides produced the record, as well. To this twenty-four hours, it remains as ane of my "desert isle discs" — I could never grow tired of it. (To heed to it in its entirety, visit YouTube.)

A way with words

Fans know that Sineád has a fashion with words, whether spoken or sung, but it too seems she's a talented writer if this memoir is annihilation to go past. Rememberings is a beautifully written book that details a remarkable life and a remarkable career in a voice that is intimate, businesslike and often wickedly humorous.

It's a volume of 2 halves: the first, written in episodic style, details experiences from her babyhood; and the 2nd, written in a different tone of vocalization, covers the flow of her life later on she became famous. This latter section is patchy rather than comprehensive (O'Connor says this is a event of her undergoing a radical hysterectomy that wrecked her retention and had a detrimental psychological impact on her life), but it inappreciably seems to matter for the tales she tells are often eye-opening, insightful and funny.

The stories from the first half are more nostalgic and often heartbreaking. She was born in Dublin in 1966, the 3rd of five children. (Her older blood brother Joseph is, of course, the Irish novelist whose work I accept reviewed here.) After her parents divorced, she and her younger brother went to live with her mother, her older siblings lived with their father.

Sineád says she was regularly and brutally browbeaten by her deeply religious mother — "I won the prize in kindergarten for being able to curl up into the smallest brawl, simply my teacher never knew why I could do information technology so well" — and she blames this abuse on the Catholic Church, which had "created" her mother. Later, when her mother died in a auto accident in 1986, Sineád, who was 19 at the time, struggled to reconcile her grief with her sense of relief.

Her musical talent came to the fore when she was sent to a Catholic reform schoolhouse (she used to shoplift regularly), where i of the nuns bought her a guitar, a Bob Dylan songbook and arranged music lessons for her. She began writing songs and after leaving school performed in and around Dublin (because she was also young to tour).

Derailing her career?

Anile twenty, she recorded the debut tape that was to put her name on the musical map. Two more albums later, merely when everything was going exceedingly well for her, with Grammy nominations aplenty and three acknowledged albums, she was ripping upwardly the Pope's movie on Saturday Night Alive.

This instance of "bad behaviour" is rather reflective of O'Connor's life as a whole: she's always been outspoken and forthright, not afraid of what people might recollect. She shaved her head very early in her career when a record executive told her she needed to exist "more feminine". She went ahead with an unplanned pregnancy when she was told she couldn't perchance exist a mother and go on tour. She said she would not perform if the Us national anthem was played earlier 1 of her concerts. And she boycotted the 1991 Grammy Awards because she did not want to support, nor profit from, the "imitation and destructive materialistic values" of the music industry.

She has always defied convention and just washed her ain matter, regardless of the consequences.

But in this memoir she paints it differently: while the media and the public viewed the Pope photograph incident every bit derailing her career, she sees it as saving her from the pop star's life she didn't want.

Everyone wants a pop star, see? But I am a protest vocalist. I just had stuff to get off my breast. I had no desire for fame.

Rememberings is a bright memoir total of cheeky spirit and forthright honesty, as entertaining equally it is enlightening. If they handed out awards for resilience, Sinead O'Connor would have to be the first in the queue. She truly deserves it.

Actress notes

I read this volume concluding year and loved it and so much I struggled to pen a review, I just didn't know how to articulate my thoughts. Then, over the Christmas pause, I started putting something together and had it scheduled for early January. I held off publishing it when news broke that Sinead'due south 17-twelvemonth-old son, Jake, had died. Today, I've dusted it off and polished a few bits, and had fun digging out some of my favourite clips to share. Forgive the indulgence.

The first is an interview on Arsenio Hall in 1991 demonstrating a very wise head on young shoulders. She talks a lot of sense and her integrity really shines through. (But how the wheels turn because, in 2016, Arsenio Hall tried to sue her for defamation but dropped the instance.)

Ane of my favourite songs from 'The Lion and The Cobra':

And, finally, her live performance at the 1989 Grammy Awards.

I've seen her in concert once — at Queen Elizabeth Hall in London in 2012 — and more recently in the queue at Dublin Airport, circa 2017. She was about unrecognisable — autonomously from the dimples and those extraordinary eyes.

hoffmancourbeacced.blogspot.com

Source: https://readingmattersblog.com/page/2/

0 Response to "The Wise Wife by Megan Ann Schreibner Book Reviews"

Post a Comment